Means-Testing and Its Consequences

One of the most dangerously seductive aspects of American welfare policy.

Back in October of 2021, the United States saw a massive uptick in the discussion around the practice of means-testing.

The conversation was initially sparked by a controversial set of demands made by Senator Joe Manchin while negotiating the details of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021, in which he championed the imposition of a means-test on the bill’s Medicaid expansion. As you can expect, his statements drew criticisms from lawmakers and laypeople alike:

Ever the opportunist, I’d like to hop on to this conversation and give some of my thoughts on the practice.

Before I start though, I should probably explain what means-testing even is.

Means-Testing at a Glance:

The term “means testing” is basically just a fancy way of saying “restricting government benefits to those who need them.” In practice, this usually translates to reducing the amount of benefits an individual or household receives as incomes rise. One of the best examples of this is the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC):

Pictured above is the benefit schedule for the 2018 EITC. The y-axis measures the amount of credit received by a household, while the x-axis measures household income. As you can see, there are three stages to the rollout of benefits:

A “Phase-in” period, where credit amounts rise as incomes rise.

A “flat” period, where the credit amount remains the same regardless of changes in income

A “phase-out” period, where the credit amount starts to decrease as incomes rise.

In the context of the EITC, the means-test would be the “phase-out” period of each schedule shown above. Essentially, the government attempts to restrict benefits to those who need them the most by reducing benefits paid out to households with higher incomes.

Similar strategies are used in the majority of the United States’ welfare programs, including the Child Tax Credit, SNAP Benefits, Medicaid, SSI, and more.

The Case Against Means-Testing:

At face value, what I’ve just described seems pretty reasonable. Why in the world would we want to give benefits to those who are already wealthy? Indeed, this sentiment has been adopted by the majority of means-testing advocates. As an added bonus, they argue, cutting off benefits to those who are already economically well-off would allow us to use that money elsewhere.

A (Tax) Burden Too Heavy to Bear

Despite how intuitive it seems at first glance, means-testing comes with a host of problems, the most serious of which has to do with marginal tax rates.

A marginal tax rate is the amount of each additional dollar of income that’s lost to taxes and transfers. If I earn an additional $100 at my job and I have a marginal tax rate of 20%, I’ll be paying 20% of that $100 in taxes. This means that the net increase in my post-tax income will only be $80.

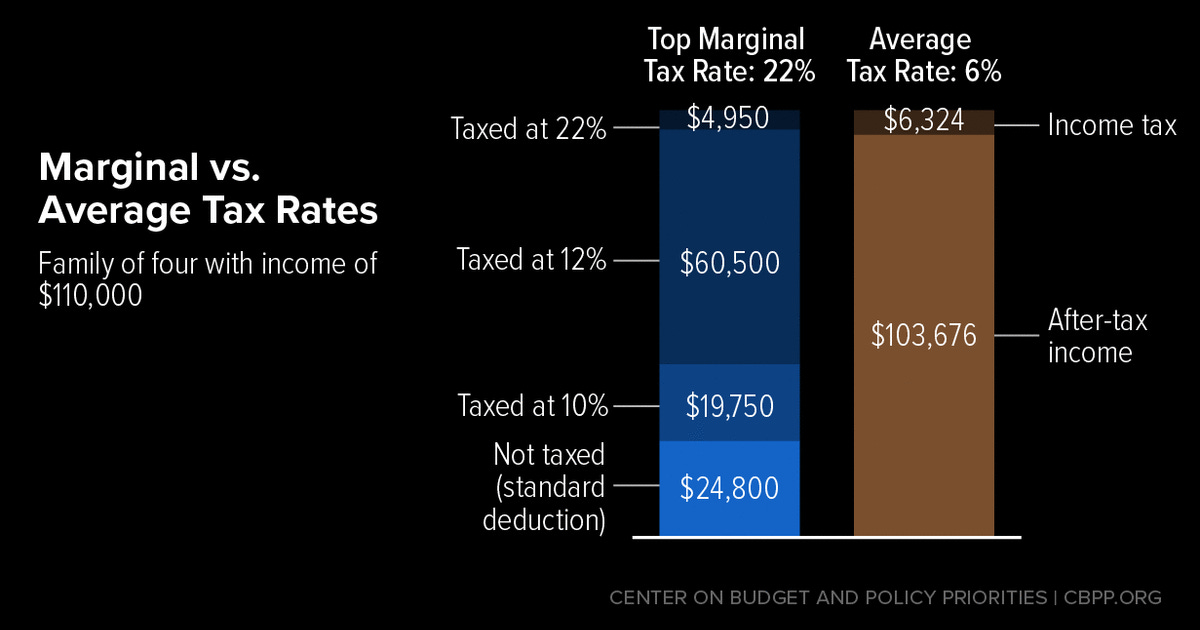

In the United States, marginal tax rates are set up in brackets that scale with income. As you earn more income, you lose a higher proportion of those earnings to taxes, creating what we call a “progressive” tax system. Here’s a nice little chart to illustrate how it works1:

Progressive tax systems are advantageous as they allow us to shift the tax burden away from people with low incomes and onto people with high incomes, whilst also creating an automatic stabilizer against economic shocks.

Means-testing throws a wrench in this whole system.

You see, what I’ve just described is called an explicit tax. The government actively collects a certain amount of money for every dollar you earn. But in order to get a clear picture of how tax rates work, we also need to look at implicit taxes. An implicit tax is a reduction in your after-tax income that doesn’t result from higher tax rates, but rather a reduction in income from government sources.

Suppose a household earns an additional $40k in income in a given year. Due to this substantial increase in income, they’ll have to pay more in income taxes because they’ve moved to a higher tax bracket. For the sake of simplicity, ignore the existing brackets and imagine that in this hypothetical they now have to pay a marginal income tax rate of 12.5%, or $5,000.

Let’s also suppose that, prior to this earnings increase, they were receiving substantial government benefits from a means-tested cash assistance program. As a result of their rising income, this benefit begins to phase out at a rate of 25 cents for every dollar earned (not too far off from the 21% phaseout rate of the EITC). As a result of this benefit reduction, they face an additional implicit tax of $10,000.

This means that, instead of increasing by $40,000, this household’s post-tax income will only rise by $25,000, with an effective marginal tax rate of 37.5%2.

The implications of this are quite clear: Means-testing imposes a high implicit tax on households that fall within the phaseout range of a benefit. This implicit tax is added onto the explicit income tax the household pays and substantially increases their effective marginal tax rate.

This problem is further exacerbated by the fact that many households receive assistance from multiple means-tested benefits at the same time, and reductions in benefits for these programs tend to stack on top of one-another.

Marginal tax rates may have the effect of dampening work efforts and the effect may be stronger when a family participates in more than one benefit program.

Here’s a graph depicting effective marginal tax rates for households with children based on their income as a percentage of the poverty line:

As you can see, effective tax rates get substantially higher as you get closer to the poverty line, with households within 100-124% of the line having marginal rates as high as 51% — meaning they take home less than half of each additional dollar of non-welfare income.

But this isn’t even the worst of it:

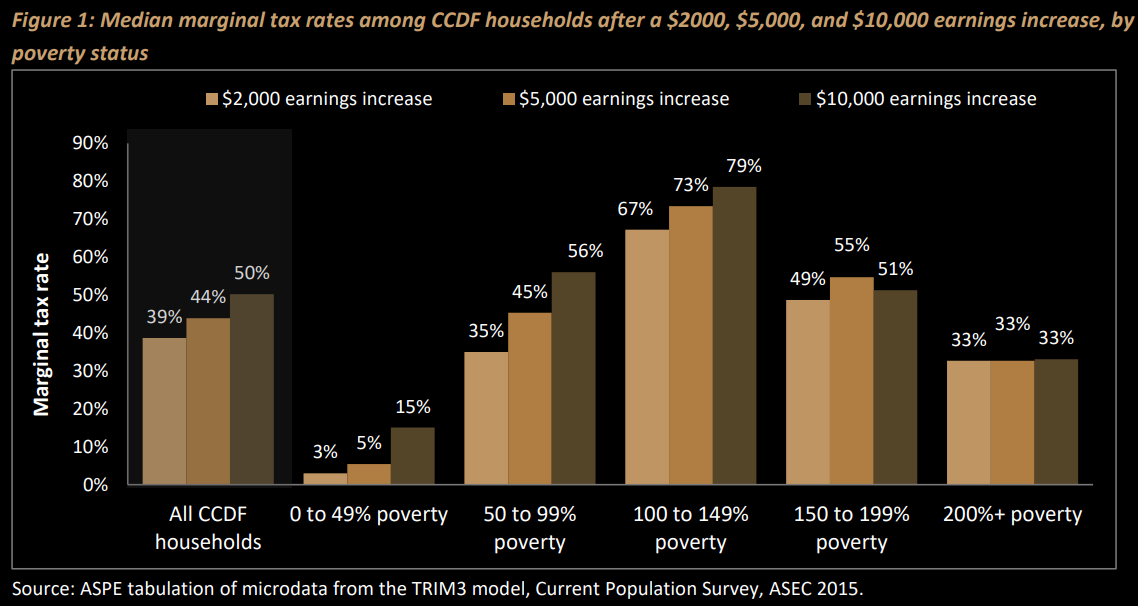

The graph above shows marginal tax rates for households that receive subsidies from the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF). CCDF Households that fall within 100-149% of the poverty line have tax rates as high as 67% for just $2,000 in additional income. These rates rise as high as 79% for a $10,000 earnings increase.

The main reason for such high rates is that many of these households receive benefits from multiple welfare programs at the same time. As I mentioned above, the means-tests for all of these programs tend to stack on top of one-another. The following chart shows the 10 most common benefit combinations and the median effective marginal tax rates for the households they cover3.

Impact on Work Incentives

“But why does this matter? Is having a higher effective marginal tax rate even a bad thing?”

I would argue that it absolutely is. Effective marginal tax rates have incredibly significant impacts on work incentives. The primary mechanism through which this happens is the substitution effect (something I touched on in last month’s post on the Child Tax Credit). Essentially, higher marginal tax rates reduce the amount of money you earn for working more (referred to as the financial return to working). This creates an incentive for individuals to reduce the amount of time they spend on their jobs, as the benefits from working more hours decrease substantially.

This reasoning is supported by the relevant empirical literature surrounding labour supply elasticities:

Combining elasticities for primary and secondary earners across the earnings distribution on a person-weighted basis, the overall substitution elasticity ranges from 0.17 to 0.37, with a central estimate of 0.27 (see Table 1).

This means that for every 1% increase in marginal tax rates, we see an approximate 0.27% reduction in the labour supply. These elasticities are further broken down for primary and secondary earners, and oftentimes vary across different income levels for primary earners (with higher elasticities at the lower end of the income distribution).

This effectively creates a “welfare trap,” in which people are disincentivised to increase their income from non-government sources as a result of means-testing, leading to a perpetual state of dependence on the welfare system — something that everyone, Democrat and Republican alike, should want to avoid.

But At Least We’ll Save More Money Right?

I hate to break it to you, but there’s evidence that suggests that even that may not be true.

In a 2011 report, Dean Baker and Hye Jin Rho from the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) attempted to calculate the potential savings generated by imposing a means-test on Social Security. The results were less than promising:

In the case of the means test that kicks in at $40,000, the total savings are 2.77 percent of the benefits paid out each year. The means test that only affects retirees with non-Social Security incomes above $100,000 would save an amount equal to 0.74 percent of the benefits paid out each year.

Depending on when the means-test begins, the money saved from introducing a phaseout of 10% could be less than 1% of what we currently spend. Raising the phaseout rate to 20% almost doubles this amount, however even these values are likely overstated as they don’t take into account any of the resulting behavioral responses (such as attempts to hide income or reductions in work-hours). The following table shows what happens when we do:

As you can see, in the event that the phaseout begins at $100,000, the savings generated after taking into account behavioral responses is just 0.07%.

The most damning part of all of this? We haven’t even begun considering the added costs associated with administering a means-test.

Currently, administrative costs for Social Security are very low, just over 0.6 percent of the benefits paid out each year for the retirement portion of the program. Administering a means test would raise these costs substantially. By comparison, the administrative costs of the disability portion of the program, which requires extensive review of applicants’ eligibility, are equal to 2.3 percent of the program’s benefits payments. If the cost of administering a means test for the retirement program raised its expense ratio to the same level as the disability program, then it would eliminate most and possibly all of the savings from a means test applied to affluent elderly.

Of course, this analysis is restricted to means-tests of Social Security, and isn’t necessarily reflective of all implementations. However, the results shown here are incredibly concerning, with means-testing potentially increasing the costs of the program due to the added administrative burden.

Lower Enrollment Rates:

There’s strong evidence that means-tested programs are also simply ineffective at properly providing benefits to all eligible households. When looking into the participation rates for most of these programs, we find that they’re much lower than we would want:

The overall participation rate of the food stamp program is 85 percent and is only 75 percent for the working poor who likely have a harder time proving their eligibility to the welfare office. The participation rate of Medicaid is 94 percent for children, 80 percent for parents, and around 75 percent for childless adults. The participation rate of the Earned Income Tax Credit (and also presumably the Child Tax Credit) is 78 percent.

This is important, as low participation rates can substantially reduce the anti-poverty effects of these programs. This is clearly shown in the difference between predicted and actual poverty reductions from the EITC:

The three tax simulators predict that the EITC lifts 4.8 million persons out of poverty in an average year (about 2.75 million children), while IRS Paid lifts 3.2 million persons, or 33 percent fewer, and this gap was exacerbated over the sample period.

In other words, the actual anti-poverty effects of the EITC are approximately 33% lower than they theoretically should be, as a result of less-than-perfect participation rates.

What causes this lack of enrollment?

One major cause is social stigma around welfare benefits. Many eligible households may be reluctant to apply for welfare programs because they believe they’ll be looked-down upon by other members of society. Strong evidence of this stigma exists when surveying eligible households who haven’t enrolled in these benefits:

69 percent of respondents not enrolled in welfare said, “A lot of people in this country don’t respect a person on welfare”

45 percent of those not enrolled in welfare perceived the application process as humiliating

Based on these results, it seems clear that a substantial portion of eligible households not enrolled in welfare benefits refuse to do so because they feel they’ll be disrespected for it.

This problem can easily be resolved by universalizing these benefits. Delivering welfare benefits to all citizens would eliminate the reason for impoverished households to fear the humiliation of being on welfare, as they’d simply be receiving the same benefits as everyone else.

In doing so, we can also address the other major cause for low participation rates: Enrollment barriers.

The application process for means-tested programs has been characterized by many as labor-intensive, requiring an in-person visit to an often inconveniently located office during limited office hours. Application forms can be confusing and sometimes must be accompanied by multiple forms of supporting documentation, each piece requiring verification. Transportation can be a problem for low-income families, especially when applicants are expected to make several trips to the welfare office, both during the initial application process as well as to respond to eligibility re-determinations, which may require additional documentation.

Through universalization, we completely eliminate this process, automatically registering all citizens to receive benefits without having to take on the administrative burden of testing the economic means of each applicant, and without having to subject them to the long and arduous application process.

Concluding Thoughts:

All in all, it seems to me that there’s truly no argument— either economic or political — that would justify the use of means-testing in the overwhelming majority of welfare programs.

Beyond the massive negative effects it has on work incentives, it appears as though means-testing is also ineffective at ensuring all eligible households have their needs adequately met. Combined with the seemingly non-existent savings generated by means-testing as opposed to universal benefits, there appear to be no valid points in favor of the practice.

Universalizing welfare benefits would eliminate every single issue I’ve brought up thus far, all for a seemingly minimal added cost.

For those who have difficulty with this illustration, here’s a simple explanation: Each shade of blue represents a different marginal tax bracket, with each being taxed at a different rate. The first $24,800 of income are taxed at 0%, as they’re covered under the Federal Standard Deduction. The next $19,750 earned after that cutoff are taxed at 10% (meaning 10 cents is paid in taxes for every dollar earned). The next $60,500 earned after the cutoff for the second bracket are taxed at 12%, and so on, with each bracket’s tax rate getting progressively higher.

Calculated by the sum of explicit and implicit taxes (12.5% marginal income tax + 25% phaseout rate).

All data comes from the 2019 Marginal Tax Rate Series created by Suzanne Macartney and Nina Chien at the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE).